Vocabulary of the Greek Testament:

Student Edition (VGNTS)

- As we can see this Stongs Plus Dictionary, does the same and also (greek to Hebrew and also Hebrew to Greek) much better. Strongs Plus Dictionary Greek Hebrew Equivalent.dctx.exe Other files you may be interested in.

- The present volume upholds his work with studies related to the syntax of the Septuagint. It is impossible to describe the syntax of the Septuagint without researching the translation technique employed by the translators of the different biblical books; the characteristics of both the Hebrew and Greek languages need to be taken into consideration.

by

Allan T. Loder

‘Vocabulary of theGreek Testament: Student Edition’ is an update/revision of Moulton’s andMilligan’s ‘VGNT’ published 1924-1930. It is based on the 1929 printedition — which is now in the public domain — along with some supplemental material from the 1930 edition. However, it isnot merely an electronic reproduction of Moulton’s and Milligan’s book.While every attempt has been made to remain true to the original content ofVGNT, the VGNTS is an major update/revision designed to make Moulton’s andMilligan’s valuable resource more accessible to a wider English-speakingaudience — especially those whose knowledge of the Biblical languages is very basic, “rusty,” or non-existent.

Greek Words and Hebrew Meanings. Compound Words in the Septuagint Representing two or more Hebrew Words. Midrash-Type Exegesis in the Septuagint of Joshua.

A reading of theprint version of VGNT suggests that the original authors, Moulton and Milligan,presupposed that their intended audience would have a high level of understanding of the Greek language. Hopefully, theenhancements in the VGNTS version will help fill the gap for those whoseknowledge is somewhat less than they anticipated.

Moulton’s and Milligan’spurpose for publishing the ‘The Vocabulary of the Greek Testament’ was todemonstrate that the language of the Greek New Testament was the common (Κοινή, Koinē) language used by ‘peopleon the street.’ The source documents used aremostly papyri and inscriptions that were discovered in the 1800s and early1900s. These include such items as personal letters, court transcripts,marriage contracts, bills of sale, petitions, etc. These give us a facinatinglook into the daily lives of those who lived around the time when the NewTestament was written. The purpose of the ‘Vocabulary of the Greek Testament:Student Edition’ remains the same as that of Moulton and Milligan, except now with the enhancements it is more accessible to a much wider audience.

The followingenhancements have been made:

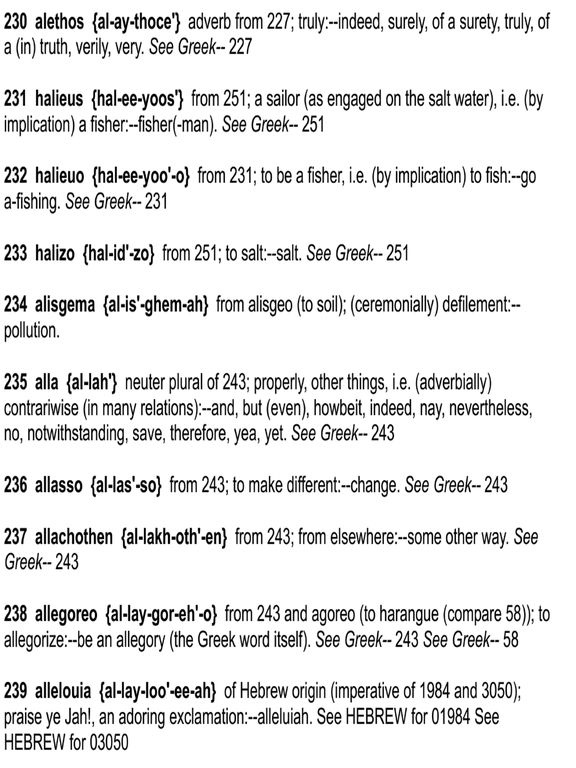

a. Eachlexical entry is keyed to Strong’s numbers.This creates a hyperlink between this dictionary module and any Bible modulewith Greek text in theWord that is keyed to Strong’s. In cases where there is no corresponding Strong’snumber, the Greek word is listed in the index. In cases where the lexical formis different in VGNT than in Strong’s, the Strong’s form appearsafter the VGNT form inside brackets with a tilde at the beginning. Forexample, αἱμορροέω(~ αἱμορῥέω).

b. For each lexical entry theGreek wordis given, followed by a transliteration, the [page number] where the word occurs in the printedition, an asterisk(*) to indicate the entry has been updated/revised, and a gloss. For example, ἀγάπη[page 2]* [agapē, “love”].

c. Allinternal cross-references to VGNT other entries have been hyperlinked. Forexample, in the body of the text of G154αἰτέωyou will see s.v.ἐρωτάω[erōtaō, “to ask”].This word is hyperlinked to G2065ἐρωτάω. Thereare over 500 such cross-references provided, thus making this module moreuseful and user-friendly.

d. Inline English translations are provided for all Greek text, as well as formost Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, Latin, French and German text. A transliteration of some text is also provided, wheredeemed helpful.

e.Inall translations of Greek text, the corresponding word for the lexical entry isunderlined in both the Greek sentence and English translation. The intent tohelp the English reader understand how that word functions in the sentence.

f.All papyri and inscriptions cited by Moulton and Milligan were carefullychecked against available print and/or electronic sources. In some cases, latereditions (i.e., transcriptions) of certain papyri have become available thathave been emended by the editors differently than what is shown in VGNT. These arenoted in the footnotes, along with the later transcriptions.

g. Over460 new lexical entries are added as a result of papyri and inscriptionsdiscovered in the decades since Moulton and Milligan.

h. Newsource materials are added to existing lexical entries, where available anddeemed helpful.

i. Pertinent information, such as units of measure, currency, names of Egyptianmonths, official titles, etc., is provided and hyperlinked.

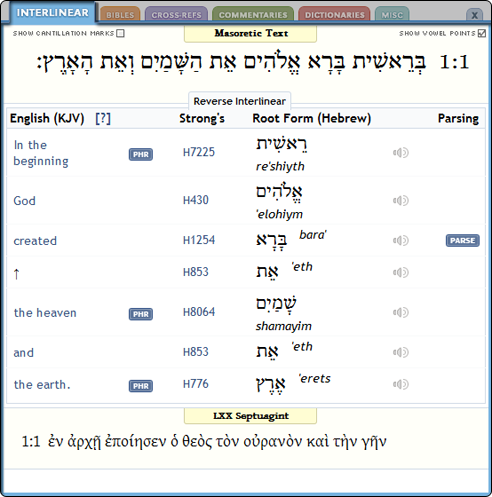

j. Incases where references to the LXX (Septuagint) are given, the text of the LXXand an English translation is provided in the footnote. In addition, theparallel Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT) reference is hyperlinked to the biblicaltext. Both references are given. For example,LXX Psa. 90:1[=MT Psa. 91:1].

l. TheVGNTS includes exerts from books cited in the print edition of VGNT which isnow either out of print, no longer available, or very hard to find.Occasionally, Moulton and Milligan redirects the reader elsewhere, withoutproviding any additional information themselves on a particular word. Forexample, for the entry Κανά (Kana, “Cana”) theyhave only “See F. C. Burkitt Syriac Forms,pp. 18f., 22.” In the VGNTS the information fromthose source cited is incorporated into the lexical entry where deemed helpful(See entry G2580).

m. Incases where the discussion on the particular form of a word centers around NTtext-critical issues, relevant information is provided in the footnotes.

n. Unfortunately, one of the greatest challenges for the student of papyrology andepigraphy is that sources are frequently listed under more that one catalogueidentifier. For example Syll 364 is no. 364 of the second edition ofDittenberger’s Sylloge InscriptionumGraecarum. But it is also listed as Syll.3797, and again as IMT SuedlTroas 573. This can be confusing andfrustrating when attempting to look up a given source. This enhanced versionof VGNT addresses this challenge by providing several additional catalogueidentifiers inside square brackets. For example, Syll 364[=Syll.3 797 = IMTSuedlTroas 573].

As I read Isaiah 22:19 recently, I had a question about a rarely occurring word in that verse. The Greek reads:

καὶ ἀφαιρεθήσῃ ἐκ τῆς οἰκονομίας σου καὶ ἐκ τῆς στάσεώς σου.

(And you will be removed from your office and from your post.)

The word οἰκονομία occurs in the Septuagint only here and two verses later. In the New Testament it appears just nine times.

A traditional lexicon (like LEH or LSJ) can give useful information about the word, but not necessarily any information about the underlying Hebrew. LEH just has, “Is 22:19-21 stewardship.” Muraoka’s work, by contrast, is a two-way index, which means you don’t get a definition or gloss (as LEH or LSJ give). What you do get, however, is what Hebrew word a given Greek word is thought to have translated. As here:

Already the reader is interested to see that the same Greek word used twice within three verses translates a different underlying Hebrew word in each case. (N.B.: I realize that in Septuagint lexicography, to speak of “Greek that translates Hebrew” is an oversimplification, as there are other textual considerations that give rise to a given “Septuagint” text.)

Then one can consult the Hebrew–>Greek portion of the index (part two of the book) to see what other Greek words (if any) are used where each of those two Hebrew words is used. In other words, Muraoka helps answer the question: did the translator of Greek Isaiah have other Greek options available to him when confronted with the Hebrew text?

Looking at Muraoka’s entry for the first of the two options above (ממשׁלה), the answer is yes:

What is of note here is that Muraoka’s work makes it possible to see at a glance what sort of translation decisions have been made in going from Hebrew to Greek text.

Greek To Hebrew And Hebrew To Greek Dictionary Of Septuagint Words In The Bible

As I study the Septuagint, I (and others) wonder about these things. How often does the Greek καρδία translate the Hebrew לבב? This breaks down into two questions: (1) What other Greek words are used to translate לבב? and (2) For occurrences in the Greek text of καρδία, what other Hebrew words might it be translating?

Muraoka writes this in the introduction:

This two-way index is meant to supplement our recently published lexicon as well as Hatch and Redpath’s Septuagint Concordance.

Up to the second edition of our lexicon published in 2002 many of the entry words had at the end a list of Hebrew/Aramaic words or phrases which are translated in the Septuagint with the entry word in question. In the latest edition of the lexicon, however, we have decided to delete all these lists as not integral to the lexicon. This set of information is important all the same for better understanding of the Septuagint, its translation techniques, the Septuagint translators’ ways of relating to the Hebrew/Aramaic words and phrases in their original text. In order fully to understand how a Hebrew/Aramaic lexeme or phrase X was perceived to relate to a Greek lexeme or phrase Y one would need to study each biblical passage, with the help of HR, to which the equivalence applies. Yet a quick overview of, and easy access to, the range of Greek words or phrases can be helpful and illuminating. Therefore we are presenting these data here separately as Part I of this two-way Index.

Greek To Hebrew And Hebrew To Greek Dictionary Of Septuagint Words Pdf

As shown in the example above, part 1 is Greek to Hebrew. Part 2 is Hebrew to Greek.

The numbers next to the Greek words above are a key to the Hatch-Redpath Concordance that Muraoka mentions. That concordance (published early in the 20th century), has all the Greek words used in the Septuagint, together with what was thought to be the underlying Hebrew. The back of the HR concordance has a list that shows all the Hebrew words (alphabetically) with the Greek words used to translate them. But you actually just get an entry like this…

אָמַר qal 37c, 74a, 109c, 113c, 120a, 133a, 222a, 267a, 299b, 306b, 313a, 329c, 339b, 365a, 384a, 460c, 477a, 503c, 505c, 520b, 534c, 537b, 538b, 553b, 628b, 757b, 841c, 863c, 881c, 991b, 1056b, 1060a, 1061a, 1139a, 1213b, 1220c, 1231b, c, 1310b, 1318b, 1423c, 1425b, 69b, 72b, 173a, 183b, c, 200a(2), 207 c, 211b.

…so that you have to go back manually through the concordance to see what words are at 37c (page 37, column c), 74a, etc. It would be tedious to look up all the Greek words translated the Hebrew אָמַר.

The second half of the two-way index more conveniently lists the above entry as:

אָמַר qal αἰτεῖν (37c), ἀναγγέλλειν (74a)…

The HR page and column references are still there, but the actual Greek words are present now.

Muraoka has also updated HR’s lexical analysis by including insights gained recently through textual criticism, new manuscripts (HR did not have the Dead Sea Scrolls), more analysis of apocryphal/deuterocanonical books, and so on.

In part one (only) Muraoka includes basic frequency statistics–how many times a given Hebrew word is what the Greek entry translates. In this index he is “content with the use of <+> symbol…when a given equivalence appears to occur very frequently.” The statistics are not comprehensive or complete, as Muraoka points out.

It’s not fair to fault Muraoka for not including a definition or gloss for his entries, since this is an index. The reader just needs to make sure to know this doesn’t and isn’t intended to replace a full-blown lexicon.

In fact, I appreciated Muraoka’s humility and realism in writing:

Our revision of HR, however, is still incomplete. Ideally, one should study each verse of every Septuagint book translated from either Hebrew or Aramaic and compare it with what is judged to be the Semitic Vorlage of the Septuagint text. This is a project for the future, and we doubt that such an investigation can be performed wholly and mechanically with a computer.

This is, in fact, the best way to use the index–with a computer and the original language texts nearby to do further investigation as needed. But even with a computer, the index is an invaluable resource and welcome contribution to the growing field of Septuagint studies. Muraoka has done a great service to Septuagint readers by publishing the two-way index.

Greek To Hebrew And Hebrew To Greek Dictionary Of Septuagint Words In The Bible

Thanks to Peeters Publishers for the review copy of this work, offered without any expectation as to the positive or critical nature of my review. The book’s product page is here. It’s on Amazon here.